How I Write

Earlier today, a friend asked me how I write. Not like, existentially or anything (although it’s a challenge these days!), more my workflows for writing. Since they’re not the first to ask this, and since I went ahead and wrote it up for them, I thought I might as well post it on here for anyone else interested in workflows that incorporate plain text, citation integrations, and open-source software.

My workflow is one that I developed early on in my graduate studies with the intention of maximizing flexibility and minimizing the temptation to fiddle with it further. There’s definitely stuff in it that only works for me because I’m willing to tolerate. It’s also one that strongly draws from a few others’: in particular Scott Selisker’s “Plain Text Workflow for Writing with Atom” and Grant Wythoff’s and Dennis Tenen’s “Sustainable Authorship in Plain Text using Pandoc and Markdown”. These lessons are honestly better and more schematic than my post, but since this space changes so frequently I thought it’d be worth having my contribution for 2020.

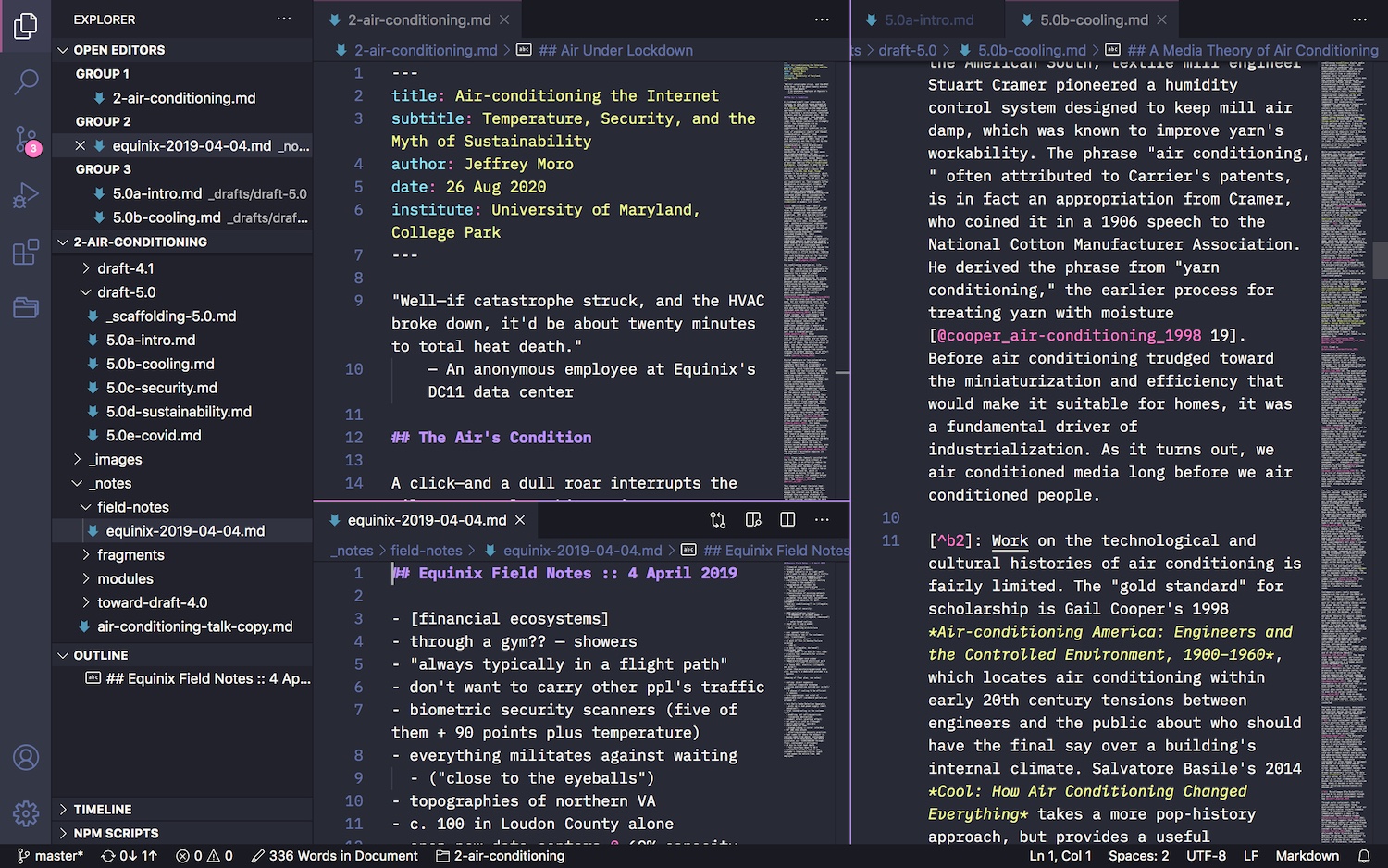

I do basically all my writing and coding and general living in a text editor. I’ve cycled through most of the major ones—Notepad, Sublime Text, Atom, and even tried my hand at emacs and vim—and have finally settled, for now on VS Code. I have no particular affection or dislike for this text editor; it just seems like the one that’s getting the most development attention at this present juncture, and doesn’t drain down my laptop’s battery.

My writing is in Markdown. So’s everyone’s these days, but it works for me. It provides me just enough markup that I can make my text useful in a variety of settings but doesn’t get too bogged down. At this point, using asterisks for *italics* is just second nature.

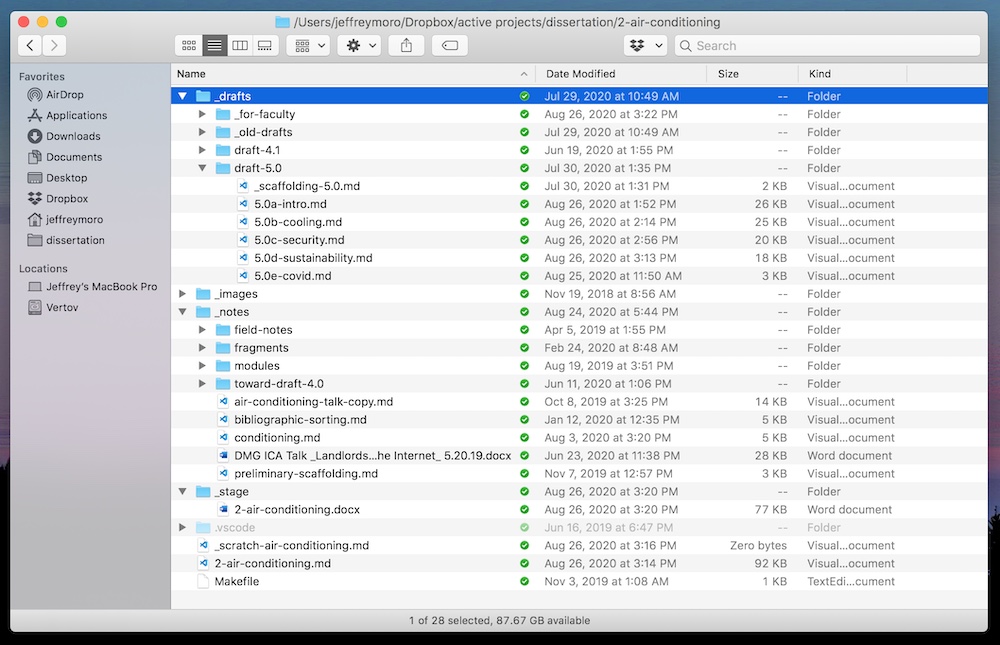

I keep projects organized in a directory structure on my computer that I manage myself. I got the idea from using Scrivener for a few years, but I hated how Scrivener locked everything within a single archive file. I wanted to be able to see everything myself—and to keep those files in a git repository, for those looking to take things to the next level of unnecessary complexity. This is what that directory structure looks like:

You can see that it’s mirrored in VS Code. I use a project manager plugin there to make switching between various projects easier. I also wrote a small script to automate starting new projects with that structure. You can download it here.

The actual writing itself is fairly uninteresting and honestly you’ve got your own style that works for you. Mine is writing by constantly rewriting and iterating new drafts, which you can tell from my directory structure. But I think the good thing about this system is it can accommodate whatever you want to design, and isn’t limited by whatever the main program (Word, Scrivener, etc.) expects your workflow to be.

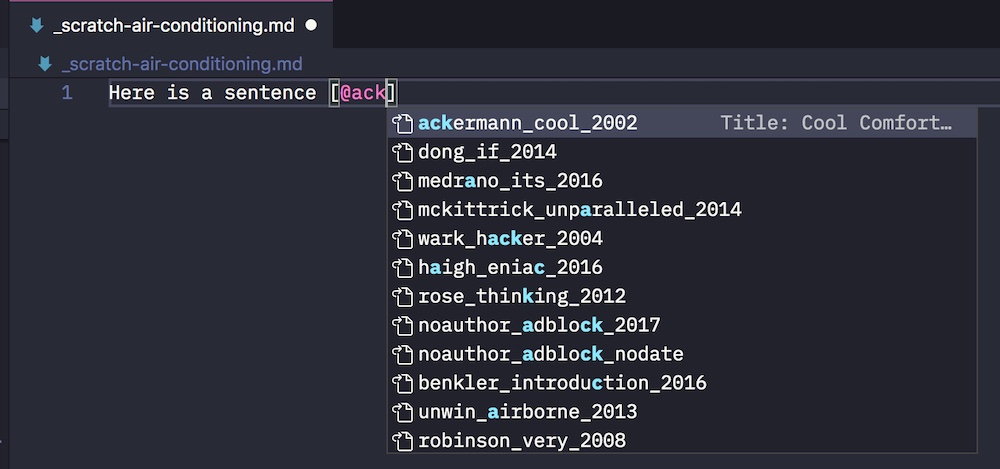

The real clincher for me is adding in citations. I keep all my citations in Zotero, which I resisted for a long time but then just took a week to make it happen and I can’t imagine life without it. In Zotero, I use a plugin called Better BibTeX, which can export my entire library in a database file with the extension .bib. This becomes the key to the enterprise. Using a plugin in VS Code (I told you it was an unnecessary complex system!) called Pandoc Citer, I can direct my text editor to that database file. I can then call up citation shortcodes from within VS Code, as such:

Now, all this looks human-readable enough, but it’s also coder garbage. Here a delightful command line tool called pandoc steps in. pandoc is amazing. I basically think it redeems computers. It can take basically any kind of text and turn it into other kinds of text. In my situation, it turns markdown files into…pretty much anything. Mostly .docx, because let’s be real that’s where academic work in the humanities always ends up.

Even better, pandoc can take those shortcodes and fill them in using information from the .bib file. Finally, if I give it a “reference” Word .docx file—basically a file that I’ve formatted like how I want my Word docs to look—it can do about 95% of the formatting of paragraphs and fonts and stuff for me. This can be all kind of overwhelming, so I adapted a makefile from sociologist Kieran Healy. Basically this is a file that you can put in your directory structure (as you can see in mine), and then run various commands based on its instructions. With the makefile in place, I can just open up the command line to my project’s folder, type make docx, and it’ll do just that. You can download my makefile here if that’s useful.

At this point, I have to open up Microsoft Word and fiddle briefly with the formatting and run spellcheck and stuff. (VS Code has a spellcheck plugin but I usually keep it off because it makes the program run slow.) I haven’t tested this workflow on something as large as a book, but it’s scaled well from seminar papers to dissertation chapters. You can also do things like include images in the markdown, but I’m a bit lazy and usually just do that in Word because inevitably there’s gonna be problems.

So that’s the immensely inconvenient Moro Method. Why do I suffer through all this? Apart from just being a tech masochist, I 1) value free and open-source tools; 2) having transparent directory structures; and 3) working in maximum plain text so that my writing is never tethered to a specific tool or platform. Despite how much I depend on a bunch of other people’s plugins, the essential information with which I’m dealing when I write are all in discrete, editable, and legible files. If I needed to edit that .bib file by hand, for instance, I could easily do so. Same if my Apple laptop kicked the bucket and I switched to Windows or Linux. And to be honest, at this point I’ve just been working like this long enough that it’s what I know.

In the end, writing workflows are only as useful as 1) they work for you and 2) they work for the people you have to work with. So far, this system feels like it’s given me the flexibility I desire while still producing media objects that are legible within the dominant discourses of academic life—that is, Word docs. And writing and thinking about writing is always a great way to avoid doing actual writing, so.