Air-conditioning the Internet

I gave this talk as a part of the ASAP 2019 conference Ecologies of the Present in College Park, MD.

This is a talk about two technologies that control the planet: air conditioning and the internet.

My project, as briefly as I can put it, is to argue that air conditioning and the internet are inextricable from each other in two senses. First, the internet materially depends on massive expenditures of energy for cooling and humidity control, without which it could not function at all. Second, and more complexly, air conditioning and the internet together constitute what I term “atmospheric media,” media for the transformation and modulation of atmospheres in both the word’s geophysical and affective senses. In particular, air conditioning and the internet depend on techniques of securitization, whereby space becomes increasingly locked down, surveilled, segmented, and subject to computational control.

So by way of a beginning, I want to take us to the closest thing the internet has to a hometown: Ashburn, Virginia.

Ashburn isn’t really a town, more of a census-designed place. Its population is comparable to the student enrollment of the University of Maryland. But Ashburn has more data centers concentrated in it than any other place on earth: 13.5 million square feet, with another 4.5 million in development, according to the Loudon County government’s website. About three-quarters of the world’s internet traffic, at some point, makes it through Ashburn.

Last April, I took a guided tour of a data center there owned by a company called ████████.

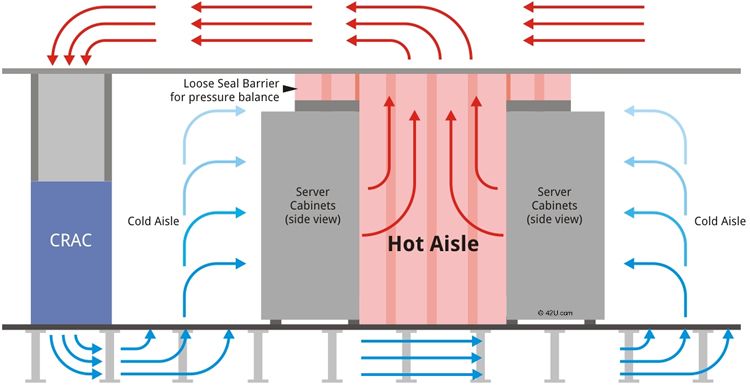

It’s loud. There’s a persistent whirring drone that the guide tells me is fifty percent the cooling fans on each server and fifty percent the enormous ventilation shafts running the length of the aisles. These shafts circulate hot and cool air throughout the data center. In order to maximize efficiency, all servers in an aisle are positioned with their fans pointing in the same direction. That aisle becomes the “hot aisle,” where hot air gets collected, cooled, and then pumped down into the other aisle, the “cool aisle.” I stand under a vent and the temperature drops twenty degrees. I had heard before coming to ████████ that no matter the weather, I should bring a warm jacket. It’s not actually as cold in there as I expected; the hot and cool aisles are remarkably contained.

I ask the guide what would happen if the air conditioning were shut off. He tells me it would never happen, because the data center has a generator and the raw materials for twenty-five minutes of extra uptime, plus a priority link into the county’s electrical grid. But if catastrophe did strike, he said, it would take twenty minutes before the temperature in the aisles rose to what he described as “total heat death.” HVAC keeps the internet alive.

Data centers are becoming popular objects of study for scholars of environmental media. They’re both anodyne and mysterious, the quintessential infrastructural object. They also concretize an otherwise dematerialized sense of the internet. Whereas the internet’s massive distribution makes its environmental effects near-unaccountable, data centers provide a geophysical fixity suitable for critique. Mél Hogan notes that data centers are among the “largest and fastest growing consumers” of natural resources, from the land they stand on, to the water they use for power and cooling, to the electricity they generate to stay online 24/7/365.

Before diving further into ████████’s HVAC, I want to take a moment to acknowledge some of my theoretical underpinnings in thinking about air conditioning as media. Temperature has a long history in media studies. We might begin with Marshall McLuhan’s notions of “hot” and “cold” media, which Dylan Mulvin and Jonathan Sterne argue introduce a kind of systems thinking to media studies that anticipates our current infrastructural moment.

One of the distinguishing qualities of thinking air conditioning and the internet together as atmospheric media is how their geophysical qualities bend ineluctably toward their affective qualities, and vice versa. Here I am thinking of similar points marshaled by Jesse Oak Taylor in his monograph on smog in Victorian literature, The Sky of Our Manufacture,

The data center’s vibe, to put it bluntly, is not chill. Here is a list of the security measures I had to pass through to reach the data center’s main floor. First, I met with the rest of my tour group in a main lobby, where we then exited the building into a small courtyard. There, I counted at least three visible security cameras. We re-entered the building via a door equipped with a biometric scanner. The guide told us these hand scanners checked ninety points on the hand, plus body temperature. Through that door, we reached another lobby, where had our photo IDs checked against a pre-approved list. We received ID badges that we were instructed to keep visible at all times. We then passed through another biometric door into a small antechamber, just barely large enough for the fifteen or so of us. The guide told us that this antechamber was designed such that you couldn’t open one door unless both the entrance and the exist were shut—a precaution both against intruders and as a firebreak. Another biometric scanner, and we were inside the data center proper, but not yet on the floor with the servers. This was just where they kept multipurpose offices and break rooms for the contractors working on the servers themselves. One more biometric scanner, and we were on the server floor. But that didn’t mean I had any access to the servers, which were kept locked inside cages. Only the clients could get inside there. The guide told us that there were further levels of security for those willing to pay for it, ranging from infrared trip wires to 24/7 armed guards. It was almost comical in its James-Bond-like intensity.

When I said that I wasn’t allowed to take photographs inside ████████’s data center, that doesn’t mean that I didn’t try. Here are two photographs that I snuck from the main floor. Admittedly, they’re unremarkable objects. The stock photos show you just as well what a data center looks like. But I think the blurriness and askew framing index the duress under which I captured these photos, the all-encompassing atmosphere of security that impresses itself upon the data center, that indeed the data center is cultivating and selling to its clients. Geographer Peter Adey offers us the concept of “security atmospheres,” wherein he argues that military security techniques since the War on Terror have become increasingly atmospheric, construed as a pervasive milieu rather than as specific technologies. On my tour, I discovered that ████████ is in the business of two kinds of air conditioning: traditional HVAC and the feeling of security.

These goals are surprisingly aligned. Historian of technology Gail Cooper writes that mid-century air conditioning engineers, enthralled with the possibility of manufacturing a controlled artificial climate, argued for hermetic, rather than permeable building designs.

I want to conclude with a paragraph from philosopher Peter Sloterdijk, who has done substantial work on air conditioning as the confluence of technical, spatial, and political concerns. In Globes, the second volume in his Spheres trilogy, he writes:

What remains common to all earth-dwellers for the time being is the planet’s active weather shell, the atmosphere in the meteorological sense, which, for well-known reasons, has become a source of concern to contemporaries. The trends on the market of climate technology have long indicated that whoever can afford to work on exiting the bad air shared by everyone does so. The residential cultures of the future will assume increasingly explicitly that livable internal climates must be created by technical means. Air conditioning, in the literal sense, will establish itself as the main space-political theme of the coming era.

12

The atmospheric media of our moment, the joint infrastructural technologies of air conditioning and the internet, constitute an intensifying feedback loop. It is a feedback loop predicated on the desire to construe a fully insulated space. I recall Octavia Butler’s prescience in the Parable of the Sower that climate collapse is also the rise of the gated community.

For the sake of putting this talk out in the public, I’ve decided to be a bit vague about which data center I went to. This is to preserve my ability to access the data center again in the course of my research, as well as not to endanger any working relationship between the data center and the folks who invited me on the tour. ↩︎

I thank Kyle Bickoff for alerting me to the specific practices of hot and cool aisle containment. ↩︎

Hogan, Mél. “Big Data Ecologies.” Ephemera 18, no. 3 (2018): 631–57, pp. 632–33. ↩︎

Vonderau, Asta. “Storing Data, Infrastructuring the Air: Thermocultures of the Cloud.” Culture Machine 18 (2019), pp. 4. ↩︎

Hu, Tung-Hui. A Prehistory of the Cloud. MIT Press, 2015. ↩︎

Mulvin, Dylan, and Jonathan Sterne. “Media, Hot and Cold Introduction: Temperature Is a Media Problem.” International Journal of Communication 8 (2014): 2496–2503, pp. 2497. ↩︎

McLuhan, Marshall. “Reversal of the Overheated Medium.” Understanding Media: The Extensions of Man. MIT Press, 1964, pp. 33–40. ↩︎

Starosielski, Nicole. “Thermocultures of Geological Media.” Cultural Politics 12, no. 3 (November 2016): 293–309 ↩︎

Taylor, Jesse Oak. The Sky of Our Manufacture: The London Fog in British Fiction from Dickens to Woolf. University of Virginia Press, 2016. ↩︎

Gumbrecht, Hans Ulrich. Atmosphere, Mood, Stimmung: On a Hidden Potential of Literature. Stanford University Press, 2012. ↩︎

Cooper, Gail. Air-conditioning America: Engineers and the Controlled Environment, 1900–1960. Johns Hopkins University Press, 1998, pp. 3. ↩︎

Sloterdijk, Peter. Globes. Translated by Wieland Hoband. Semiotext(e), 2014, pp. 961. ↩︎

Butler, Octavia E. Parable of the Sower. Four Walls Eight Windows, 1993. ↩︎