Decaying Plastic Play: <em>Flappy Bird</em>’s Hacked Afterlife as Media Archaeological Praxis

This is a short talk I gave at Digital Humanities 2017: Access / Accès in Montréal. It was part of a panel called “The Environmental and Human Costs of Digital Humanities,” and is a revised version of a blog post from this very site.

For those interested, here’s a link to the printed abstract for this talk, which shares much of the same conceptual ground but offers slightly different citations.

1990: Nintendo releases Super Mario World for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System.

2013: Vietnamese games developer Nguyen Ha Dong releases Flappy Bird to the iOS App Store.

2016: Prolific YouTube streamer SethBling releases a video demonstrating how, using a series of glitches and graphical exploits present in the console original of Super Mario World, he transformed the game into an ad hoc computer, and with timed jumps and button presses, wrote three hundred and thirty-one bytes of data into the console’s RAM—data corresponding to the original source code of Flappy Bird.

SethBling’s hack then produces a chimeric object; a hybrid of plastic, logic, and time; the ghost of one game haunting the shell of another. This haunting, I will contend over the next eight minutes, constitutes a regenerative practice: a “circuit bending,” to draw on a theoretical and practical challenge from Garnet Hertz and Jussi Parikka.

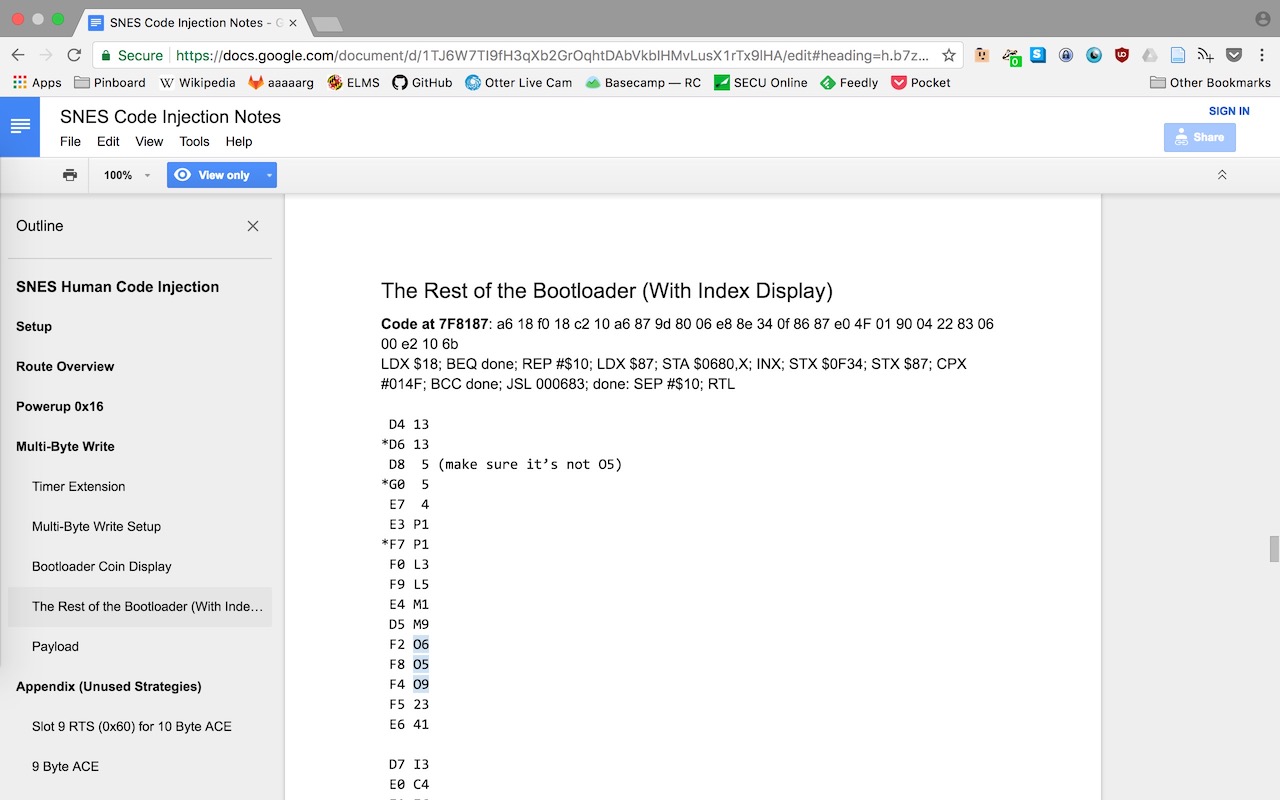

So first, let’s break down how this hack works, and I recommend checking out SethBling’s video for a more detailed description. This hack relies on “arbitrary code execution,” which is precisely what it sounds like: massaging the game to the point where it can execute code it’s not supposed to. First, SethBling attaches a number of peripheral controllers and tapes down their buttons, clearing out a cache of otherwise-unused memory in the console itself. Then, he executes a series of baroque glitches that put the game in a receptive state, where it’s ready to write values to that cleared cache. And then, he writes a payload into the cache itself, carefully timing and positioning sprite movement on the X-axis to correspond exactly to each hexadecimal value of assembly code. This process takes about an hour. Finally, after he writes those three hundred and thirty-one bytes to the cleared cache, he executes the payload with an arbitrarily selected action: in this case, collecting a 1-up mushroom. The game then immediately switches into Flappy Bird mode. As a comment below the YouTube video asks, “So does this mean that Super Mario World is a programming language now?” And the answer is more or less: yes.

This is next-level circuit bending: by breaking Mario past the point of regular playability, SethBling paradoxically makes the software superfunctional, capable of receiving input and executing output far beyond the boundaries of the designers’ original intentions. But I want to nuance what I see as a political positivism underneath this kind of reading, one that leads towards a pseudo-accelerationist viewpoint, over-valuing the act of breaking rather than repairing. This hack works not because of any raw power within the computational object or the sole genius of its hackers, but rather how it incidentally reveals affinities between its two subjects, Mario and Flappy Bird. And, following Wendy Chun’s work on computational memory, I propose that these affinities betray the repetitive simultaneity of computational time, proposing instead regimes of ephemerality undergirding systems we imagine to be stable.

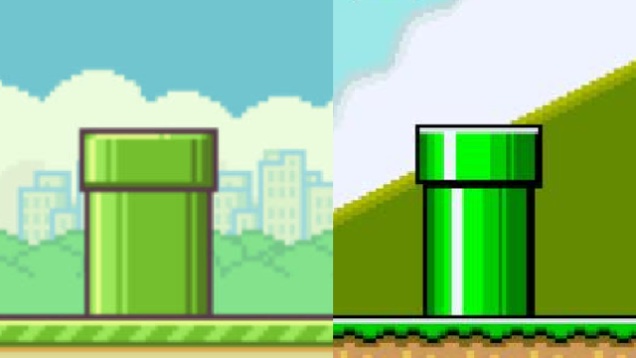

When Flappy Bird first hit it big in early 2016, media outlets like Kotaku noted not just its broken difficulty, but also how it transparently rips off Mario’s aesthetics. That the game was the product of a single person’s labors, a single person in Vietnam to boot, well outside the culturally acceptable Anglo- or Japanospheres of games development, further contributed to the public’s sense that this game was some kind of illegitimate bootleg. (That this person pulled the game at the height of its profitability also is a kind of perversion.) Now, it’s inarguable that Flappy Bird does rip Mario’s visual aesthetic off, and even the flappy sidescrolling mechanics are appropriated from a mix of online Flash games.

But this theft actually makes it all the more ingenious that Flappy Bird, of all possible games, emerges from Mario’s hacked ruins. On the one hand, there are few games more unlike Mario: Flappy Bird is crude, maddening, and has no sense of proper monetization in a capitalist economy. But by wedding the original to its copy, SethBling ends up being programmatically and artistically astute: he can both save on valuable RAM space by ripping off the original graphics yet again, as well as confound our sense of original and copy by ripping off the original in order to vindicate the rip-off itself. And this also cofounds our sense of time: the future’s crude broken core beats within the past’s polished heart, and a game forcibly disappeared at the height of its popularity emerges within one that, through the coercive machinations of Big Nostalgia, continues to endure. Moreover, the hack itself is a kind of deliberate decay, one that deforms the digital object until it becomes pliable, manipulable, and inscribable. Much like the ABS that comprises its cartridge shell, the game becomes plastic: transformable, recyclable, and pliable under the right (industrial) conditions.

At its core, this hack asks us to confront the mechanisms by which we articulate the value of media, particularly as a function of time. It creates a doubled-back, collapsed, and repeating temporality, one that shares more than a passing familiarity with what Wendy Chun describes as software’s “enduring ephemerality.”

This hack stages decay, but also surprising new life—new platforms, new possibilities for inscription and play. In her most recent book, Updating to Remain the Same, Chun proposes that the undead of information, its ephemeral roving repetition, constitutes a Derridean deferral.

Super Mario World [ROM]. Nintendo. “Super Mario World (USA).sfc.” 524 KB. HiROM. [789C0042 9C0C429C 0B429C40 219C4121]. ROM modified 24 Dec. 1996. Game originally released 1990. Emulated in OpenEmu 2.0.5. ↩︎

Nguyen Ha Dong. Flappy Bird. iOS, released 24 May 2013. ↩︎

SethBling. “SNES Code Injection – Flappy Bird in SMW.” 28 Mar. 2016. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hB6eY73sLV0. Accessed 16 Aug. 2017. ↩︎

Hertz, Garnet, and Jussi Parikka. “Zombie Media: Circuit Bending Media Archaeology into an Art Method.” A Geology of Media, U of Minnesota P, 2015, pp. 147–54, 144. ↩︎

Jackson, Steven J. “Rethinking Repair.” Gillespie, Tarleton, et al., editors. Media Technologies: Essays on Communication, Materiality, and Society. MIT P, 2014, pp. 221–40, 221. ↩︎

Nixon, Rob. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Harvard UP, 2011, 65. ↩︎

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Programmed Visions: Software and Memory. MIT P, 2011, 148. ↩︎

Chun (2011) 10. ↩︎

Chun (2011) 133. ↩︎

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. MIT P, 2016, 91. ↩︎