~/jeffreymoro/blog/2026-01-07-roundup-2k25

Good afternoon Moronators. Class is not in session (UMD is blessedly still off for a few weeks yet). We are seven days into the new year and so much has already happened. We are at war(?) with Venezuela(??) or Greenland(???). My best friends had a baby (her name is Dorothy) (the baby, not my best friends) (although soon the baby will be my best friend too). My cat has learned how to jump onto the kitchen counter. It’s shaping up to be one hell of a year.

But we’re going to ignore all of that for now, because this is a roundup post for 2025, a tire fire of a year during which nevertheless I experienced great personal growth and wrote a few things that I’m pretty proud of that I am going to shove into your inbox here on a Wednesday in January, because if there’s one thing I never learned how to do it’s execute a proper newsletter posting strategy. But to tell the truth, if I might expound for a moment (and what else is blogging for after all): it’s not like anyone else has any other strategy for how to write and share work on the internet or anywhere else anymore. I am not going to get all meta here (recall: this is a central promise of this blog) because I don’t need to tell you about our utterly degraded information environment in the year of our lord twenty twenty-six. You’re reading for Christ’s sake! You already know how bleak shit is out there. That being said I did receive the other day a very nice email from a stranger who had found my posts on a website called minifeed.net, which collects olde timey blogs just like this one, so perhaps there is hope for the written word on the internet after all.

Anyway enough of all that. Let’s get down to brass tacks. Here are some things I wrote last year:

simulation games in the stratosphere

Already I am cheating because this was a conference talk, not something published. But! I had a grand time at the Society for Cinema and Media Studies (SCMS) conference in Chicago in March, where I gave a talk titled “Simulation Games in the Stratosphere,” all about the 1990 video game SimEarth: The Living Planet. In the olden days (grad school) I made a point of posting the text of my conference talks on my website. I don’t do this anymore for reasons of fashion and mystery, but I wanted to share a lil taste here:

In 1990, the video game production studio Maxis released its first follow-up to its 1989 smash hit SimCity, a game titled SimEarth: The Living Planet. Whereas SimCity offered players the opportunity to model the comings and goings of an urban landscape, SimEarth expanded on its predecessor’s scope dramatically, simulating the geological and climatological development of a planet over billions of years, with striking mathematical complexity and granularity. Players develop planets through a range of scenarios, from the primordial magma of Earth’s earliest days, to the emergence of intelligent life, to expeditions to terraform planets modeled after Venus and Mars. Maxis’s chief developer Will Wright collaborated on the game with James Lovelock, an English scientist best remembered for his controversial “Gaia theory,” which contends that a planet’s biosphere functions as an “active adapter control system able to maintain [said planet] in homeostasis” (Lovelock and Margulis 3). In other words, feedback from a planet’s living organisms might substantially influence and maintain favorable climatological conditions. SimEarth takes an explicitly pedagogical view of its simulations: “it is a game, an educational toy, and an enjoyable tool,” writes technical writer Michael Bremer in the game’s substantial DOS user manual, wherein “life, climate, the atmosphere, and the planet itself . . . all affect each other” (2).

In this talk, through a case study of SimEarth, I want to explore some formal relationships between climate modeling and gaming, both at the level of software implementation as well as aesthetic experience. I am chiefly interested in SimEarth as a game that one plays — or, as we shall see, that plays itself — and subsequently what SimEarth has to teach us about the notion of playing with climate, what such play entails and what its object might be. I define a genre of “climate simulation games,” which encompass scientific tools, video games, tabletop games, and other media objects, all which participate in a broader media-scientific history of atmospheric simulation. Through SimEarth, I’ll articulate a strategy of “climatological play” that undergirds this genre, a type of play that hinges on the manipulation of climatic variables towards a desired outcome, whether eco-utopian flourishing or total collapse. It’s in the balance between these two outcomes — flourishing and collapse — that I locate my argument today. For, following Jean-Thomas Tremblay’s and Stephen Swarbrick’s recent call in their book Negative Life to think against the environmental humanities’ habitual valorization of interdependence, generativity, and nature as what they call a “benevolent pedagogue,” I am most interested in how playing SimEarth overwhelmingly models ways for planets to die rather than to live. Failure, I’ll contend, over and against the pedagogical project of its creators, is SimEarth’s default end-state. I’ll track this notion of SimEarth’s failure — as a game, as a simulation — across its programming and gameplay experience, suggesting ultimately that the project of its climatological play is less to teach we humans how to care for the planet, and more to articulate how planets are themselves monstrous, non-human intelligences — intelligences that, even in simulation, evade human attempts at command or control.

I shared this talk on a panel with my colleagues Nick Silcox, Sam Kellogg, and Megan Wiessner, who are all uniformly brilliant and whose work you should check out.

algorithms and the occult

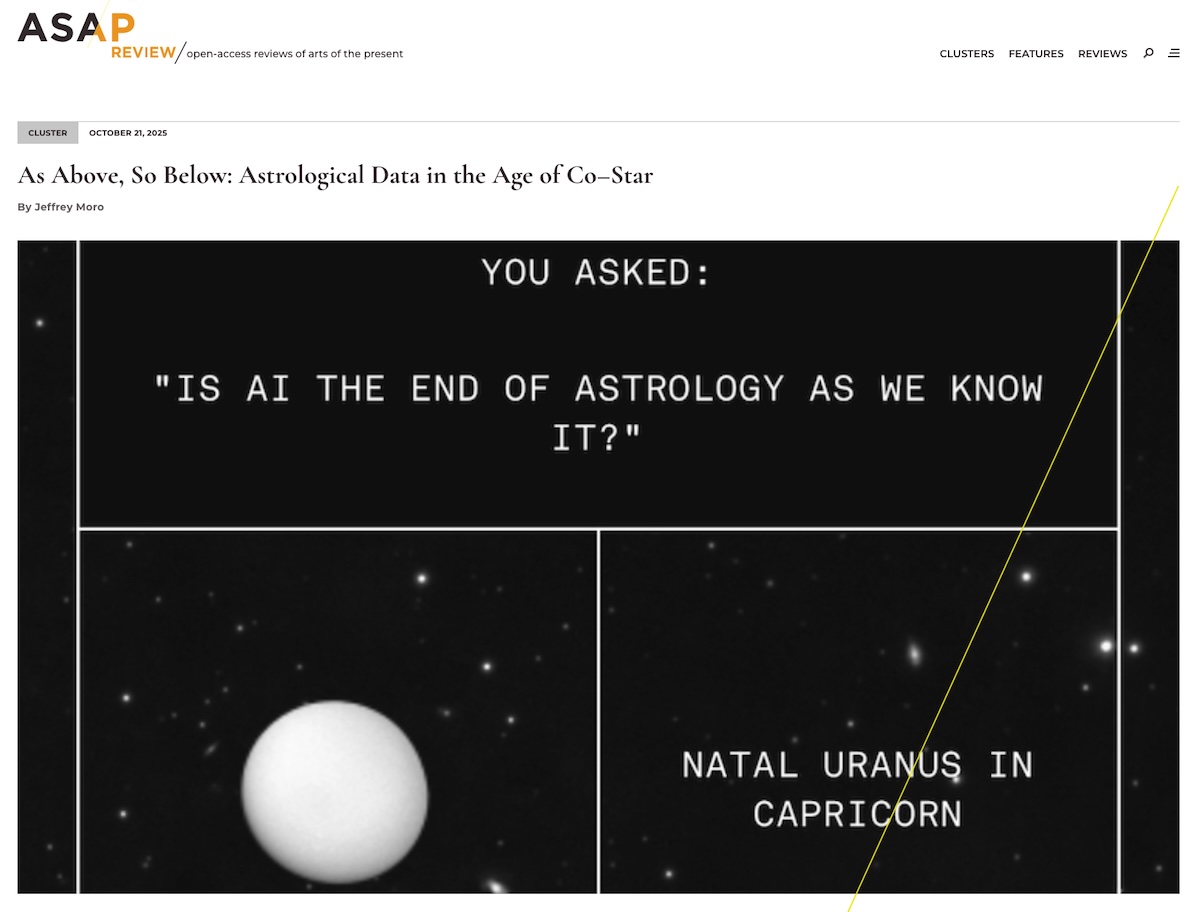

Ok back to the actually published stuff. My biggest project this year was co-editing a research cluster for ASAP/J, the journal of the Association for the Study of the Arts of the Present, with my colleages Tamara Kneese and Briana Vecchione, titled Algorithms and the Occult. Tamara and I had been daring each other for years to do something on this theme, so it’s especially fun to see it out in the world. All the essays are worth your time; mine is titled “As Above, So Below: Astrological Data in the Age of Co—Star.” Here’s a taste:

I am a Cancer sun, Sagittarius moon, and Capricorn rising. My Mercury is in Cancer, which means my intellect is emotional and empathetic. I have Leo placements in Venus, Mars, and Jupiter, which indicates an extroverted nature. My Saturn is in Aquarius, which means that I am implacably stubborn; that Saturn is in my first house also means that I have trouble with my self-image. My Uranus and Neptune are in Capricorn and my Pluto is in Scorpio, traits that I share with those born in the first years of the 1990s. Collectively, we are responsible, serious, and hungry for power.

Whether any of this rings true I will leave to my friends and family to decide. I learned these placements and their interpretations through Co–Star, darling astrology app of the terminally online. Billing itself as “the astrology app that deciphers the mystery of human relations through NASA data and biting truth,” Co–Star achieved widespread popularity during the Covid-19 lockdowns, claiming by the summer of 2023 over 30 million registered users. The app’s pleasures are not hard to grasp. Its chic, monochromatic design breaks from astrology’s historic shawl-clad mysticism. Its snarky push notifications ignite a millennial limbic system trained on shitposts. And crucially for this essay, the app surfaces a wide array of astrological data, offering a panoply of potential interpretations of, influences on, and explanations for the daily torment of modern living. These data, Co–Star takes pains to trumpet in its marketing, draw from information collected by NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory at Caltech, alongside the work of human astrologers and poets. All these numerical and textual data enter the black box of artificial intelligence and emerge as horoscopes.

Oh, and for those who are podcast-inclined, I joined Jul Parke of the University of Toronto on her new podcast Love + Machines to talk about the project. Here’s the link: come for the astrology, stay for me getting into why the post-2008 zero interest rate policies are the root of all evil.

measuring the sky from the curve of the earth

Finally, I contributed a chapter to a new edited collection on landscape architecture and environmental media, edited by Karen M’Closkey and Keith VanDerSys of PEG Office of Landscape + Architecture. The volume is titled Media Matters in Landscape Architecture and my chapter is titled “Measuring the Sky from the Curve of the Earth.” Karen and Keith put together a lovely collection of both media theorists (me!) and practicing landscape architects (not me!) to think together about how media constitute natural and built environments alike. My chapter is about weather stations:

While individuals have maintained weather records throughout written civilization, weather stations emerge in a recognizably contemporary form in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. They arose in part due to two historical and scientific tendencies: first, the invention of scientific instruments capable of measuring such qualities as temperature (the thermometer), humidity (the hygrometer), and wind speed (the anemometer); and second, a political drive to establish territorial control over newly expanding empires. In the United States, for instance, the first weather station networks were volunteer organizations that submitted observations in a tabular format to a central office run by the Smithsonian. In 1870, President Ulysses S. Grant signed a joint congressional resolution creating the Weather Bureau, the ancestor of today’s National Weather Service. Under the auspices of the Secretary of War, a testament to how weather data were considered complex and vital enough only to be entrusted to the armed forces, the Weather Bureau was tasked with “[taking] meteorological observations at the military stations in the interior of the continent.” Nevertheless, as historian of science Philipp Lehmann notes, the early stages of meteorological development were marked by a disjuncture between “the global vision” of data standardization and the messy physical realities of meteorology in practice: broken instruments and untrained observers alike stymied attempts to collect useful and consistent data. With the development of computational weather prediction in the 20th century, weather stations became increasingly sophisticated nodes in a digital network. New kinds of sensing technologies alongside their concomitant miniaturization further multiplied weather stations and made their operations possible in more challenging environments, from far-flung islands to inner cities. However, the distribution of weather stations is still imperfect, leading to elisions in the data they collect. Furthermore, their operation is contingent on proper geographic siting, to say nothing of mitigating signal interference from both human-made and natural causes. As media technologies, weather stations are thus in continuous conversation with the landscapes in which they operate, not simply as observers of conditions, but as active participants in the construction of meaningful weather data.

This chapter explores the formal relationship between weather stations and the landscapes they mediate. In it, I argue that weather stations as media technologies themselves are key to a meteorological project of distinction – that is, distinguishing between those environmental phenomena that will produce meaningful data and those that are statistical noise or interference. Articulating these distinctions entails a range of media techniques for the calibration of landscapes, from site selection to ongoing landscape management, which in turn influence a station’s capacity to collect “good” data. Furthermore, just as technical instruments mediate landscapes, so too do landscapes leave their traces on instruments themselves, wearing them down over time and leaving friction and gaps in the meteorological record.

***

It’s a false spring today in Baltimore, the kind of day that inspires both relief (from the nasty business of winter) and dread (why am I walking around in a T-shirt in January?). But as Beth Orton sings, “spring’s beneath the snow in bud”: