Roomba in Revolt: Sociability and Securitization in the Internet of Things

This is the text of a talk that I gave at SIGCIS’s 2017 conference, “Command Lines: Software, Power, Performance” in Mountain View, CA at the Computer History Museum. I was part of a panel on “The Fiction of Neutral Tools,” the video for which you can see here. For those who like to read, a transcript follows.

October 21st, 2016

On Friday, October 21st, 2016, the Internet went down.

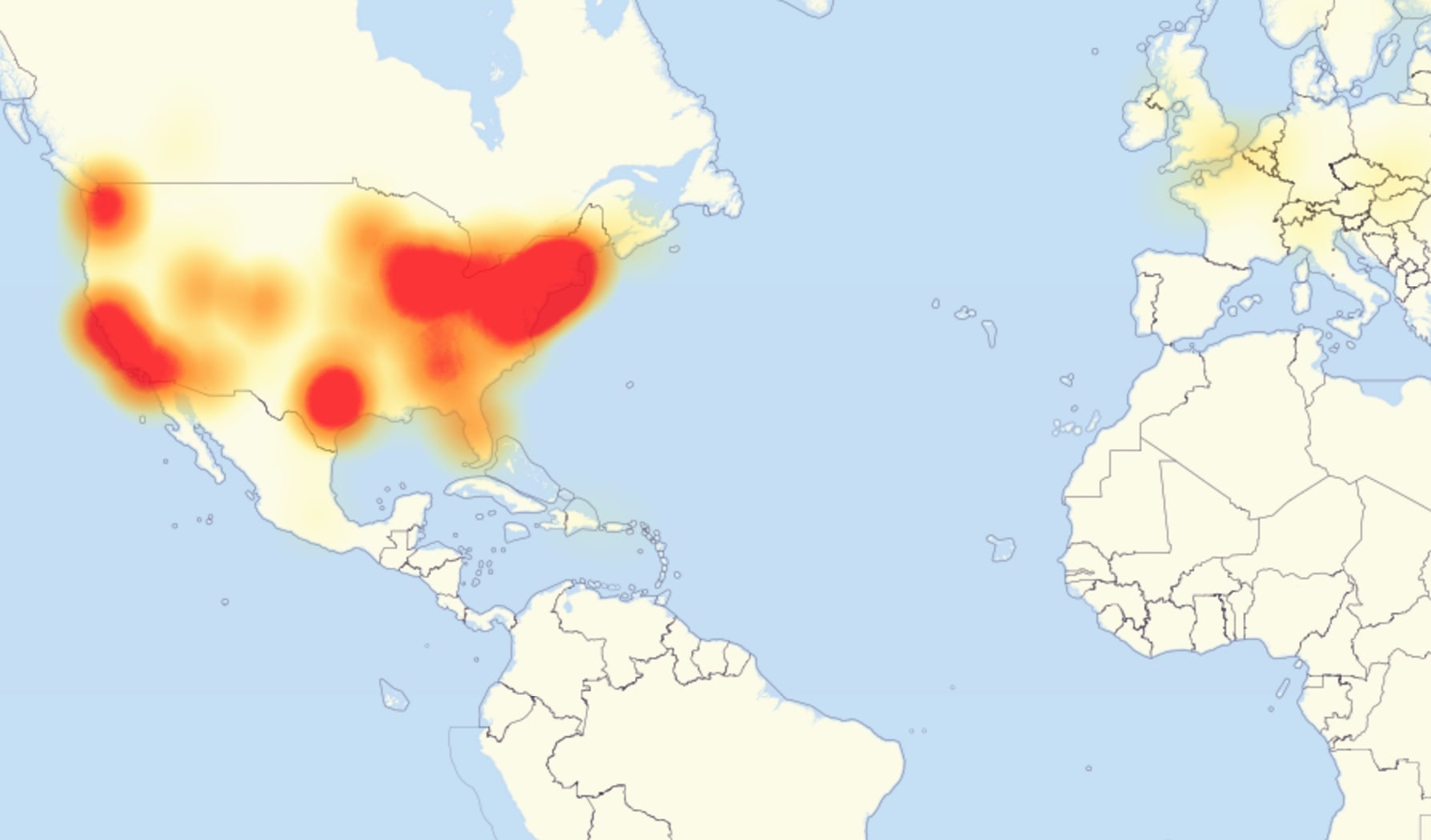

Not the whole Internet itself, of course, and only for the areas you see on this map, but for those folks many of the major sites that structure our experience of the Internet—Twitter, Github, Netflix—all threw up server errors for much of that day. When the dust cleared on Saturday, security researchers placed the blame on an unprecedentedly large distributed denial of service attack, or DDoS.1

The target: Dyn, a New-Hampshire headquartered Domain Name System provider. Dyn’s one of many companies in this space, which provide the tech through which user-legible domain names translate into machine-legible IP addresses. In other words, this attack affected such wide swathes of the Internet because it targeted centralized infrastructure, rather than individual sites. But what makes the Dyn attack central to my talk today is not its record scale, but rather how it achieved such size. It worked by exploiting vulnerabilities in Internet of Things devices: webcams, smarthubs, toasters. These networked objects, while low-powered, have strength in numbers, as the Mirai botnet, which powered the Dyn attack as well as a number of other record-setting attacks last fall, demonstrates. So this is a milestone of sorts: we have officially entered a reality in which the smart lightbulb you backed on Kickstarter or your klutzy Roomba might in face be weaponized against you.

Sociability and Securitization

I offer this weaponization as a way to understand our emerging relationship with these smart objects, and what we construe as the Internet of Things more generally. The Dyn attack is evocative for me because it stages a conflict across two registers: sociability and securitization. “Sociability,” in that it foregrounds the kinds of entanglements in which we find ourselves with these objects both on the level of social life and communication; “security” in the very real sense that we are made open to attack by and through these objects.2 Entanglements are mutual, and I contend today that we humans are as sociable with these objects as they are with us or with each other. Moreover, “sociability,” framed as a messy and intimate exchange of energies across bodies and things, operates across human and nonhuman registers, with the Internet of Things operating as a cross-pollination site. Framing relations like this allows us to consider the Dyn attack less as a mass deviation—an incursion in a clean network—and more as the amplification of capacities always already latent in the bodies and objects that together articulate an Internet of Things. “Securitization” is then an attempt to regulate these energies. But we run up against a technical paradox. As theorist Wendy Chun reminds us, our devices operate by promiscuously leaking information: constantly transmitting and receiving signals.3 I want to extend this to us humans as well. It’s then this tension, between the capacity to socialize and leak and how such capacities leave us vulnerable, which is the heart of my paper today.

Revolv

So let’s start with substantiating that first claim: that we are messily entangled with the Internet of Things, and indeed participate fundamentally and equally in it alongside objects.

In its simplest form, an IoT object grafts together a pre-existing technical object, like a mouse trap or a toy doll, and a computer. These computers, as we know, are usually quite small and low-powered. They’ll often connect to environmental sensors that allow the object to respond dynamically to a variety of factors, like its environment and the operation of other networked devices. These individual nodes are often controlled by smart “hubs,” more sophisticated computers that orchestrate all these data flows. And these smart hubs usually displace their interfaces onto one other familiar hybrid: your phone.

So by way of practical example, let me give you one user’s description of IoT in action in his own home. This is Arlo Gilbert, writing in 2016 about his Revolv smart hub:

“I am a home automation nut. When I arrive home my lights turn on. In lieu of motion detecting lights, I have a Z-wave motion detector that notifies my Revolv when there is motion on any side of our home and turns on the appropriate lights. Although I do set a home alarm, there is really no more effective vacation security than the programatic turning on, dimming, and turning off of lights in a manner that would indicate that people are home. After buying my Revolv I put my outdoor landscaping light on it and threw away the old timer. Now at Sunset my landscape lighting turns on. Holiday lighting does the same. It’s magical.”

Sounds like EPCOT, right? (Parenthetically, some of you may know this piece because Gilbert wrote it in a rage after Google announced it had bought out and was shutting down Revolv’s servers, effectively turning his smart hub into a, quote, “container of hummus.” I draw our attention to who owns what here.)

Gilbert’s dream is a good example of the promises that IoT makes for our lives. I love the play of light here, which responds to movement and time. This play, moreso than anything else in the passage, creates friendly, livable, and safe domestic space. And not only can Gilbert’s home respond to motion or time, but through light it can appear to simulate someone living there even when no one’s home. This is the dream of IoT self-sufficiency: a system that can function independently, inscribing the human body as a negative space, perceptible and reconstructable as the sum of a body’s traces on the space. To use the EPCOT frame again, the human becomes a kind of special effect.

Internet of Assemblages

We are all acutely aware of the traces that we leave on the Internet and the negative images Facebook and the NSA can construct of us. The Internet of Things then applies these principles to a particularly fleshly register: bodies become data—even when bodies have to be sensed indirectly, or simulated. Philosopher Yuk Hui, following Gilbert Simondon’s work on technical objects and networks, argues that the emergence of the digital object—the email, the social media profile, the structured .xml document—heralds a multiplication of relations that concretize into what he calls “the digital milieu.”4 This “milieu,” a term appropriated from Simondon, constitutes the networks of networks of relations that propagate across digital objects—and indeed, comprise digital objects themselves. A key feature of the emergence of such a milieu is the emergence of “protocols and standards,” which, when complied with, allow different objects to make themselves known to other objects. The Internet of Things doesn’t invent new protocols, necessarily (although perhaps it should), but I note that in wrapping itself up so tightly with our incarnate bodies and domestic spaces, it offers tangible benefit primarily to those who remake their selves following its protocol. I think here of Halcyon Lawrence’s talk earlier this morning foregrounding of the particular vocal affects we use when communicating with Siri or Alexa as an attempt to make ourselves legible to these objects, or how we comply with the directive to make 10,000 steps on our FitBit—an arbitrary calculation that nonetheless reshapes how we move through space.

I come back now to the question of Being: what are the lives circulating and comprising this milieu? Instead of a clean, spare, addressable network, the Internet of Things presents a fleshly, volumetric, constantly-reorganizing assemblage—language through which I want to defer as much to Deleuze and Guattari as to Donna Haraway. Such a framing, particularly that of Harawayian cyborg, or perhaps better “companion species,” helps us begin to see the sensory capacities of computationally-enhanced objects as actually decoupled from computation as such. In this claim I draw on Kari Kraus’s work on what she calls “enchanted things,” a different term for computer-thing hybrids.5 She observes that physical objects “are already lo-fi sensors in the natural state,” for example, a book that grows moldy in response to humidity, or that records waxy traces if read by candlelight. With the frame of the assemblage, it makes sense to then talk about the “sociable” work of the Internet of Things as marshaling constantly shifting productive capacities, energies that are not necessarily human or object or computer, but rather emerge from and flow along channels of material specificity and political possibility. I call these acts “sociable” to do two things:

- to highlight how, through the addition of computation, we are making legible in objects communicative capacities that we previously imagined to be just the province of humanity, and

- to decouple these capacities from the realm of the exclusively human or the computational and to begin to articulate how “sociability” manifests as a concrescence of energies that indeed produce an object’s objectness, of sorts.

The computer becomes a tool through which these capacities are intensified and channeled in certain ways, as much for us as “users” as for the objects as “the used.”

Mirai

I’ve spent this time on sociability so that we articulate how it bears on the specific vulnerabilities that the Mirai botnet exploits. The word “mirai” is, ominously, Japanese for “future.”

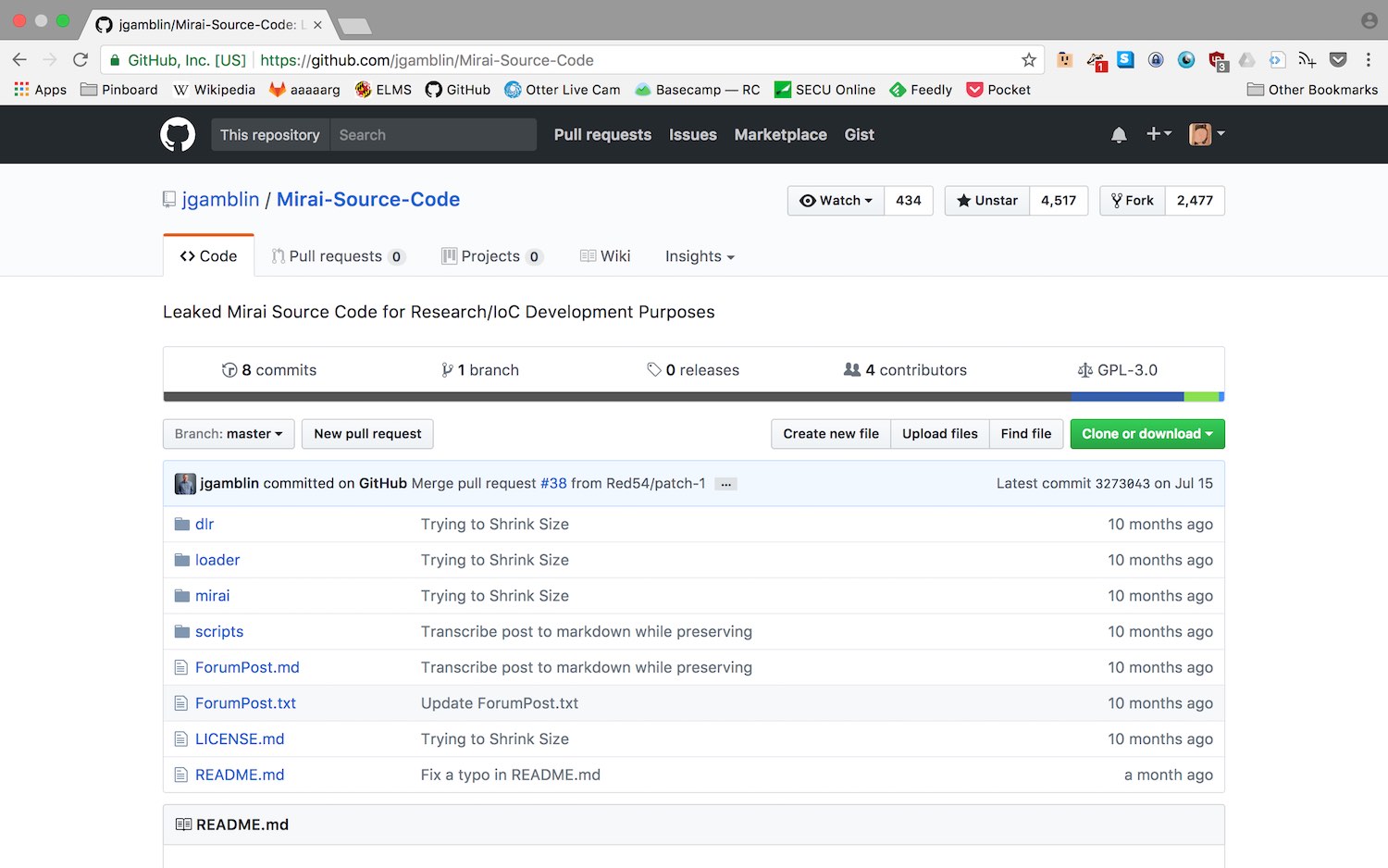

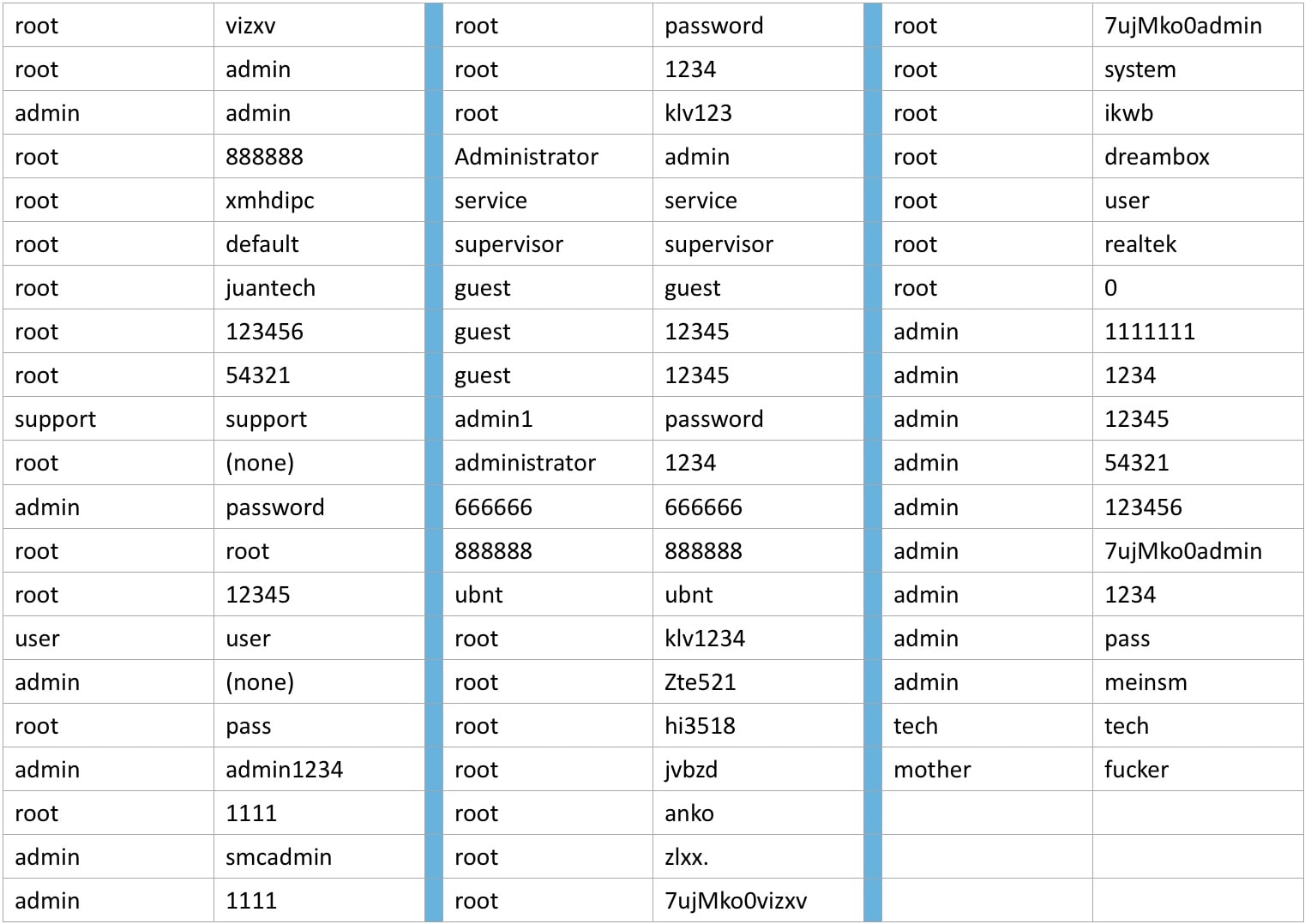

After the wave of attacks last fall, its source code was posted GitHub, so we can see that it’s actually pretty crude code in the end. A compromised device operates normally but continuously scans the public Internet for a range of IP addresses corresponding to other IoT devices. Once it finds a target, it uses a dictionary attack of the sixty-two most common default usernames and passwords for IoT devices to break through.

Its operation is basal-level, the purest ideology of the Internet of Things, both on the level of technics—one thing pinging another thing—but also on the level of construction, in that its operation depends on the flawed work of end-users who never change their passwords or manufacturers who never give users that opportunity. We come to see these tactics as not categorically different than normal operations. This is an attack of excess and purity, of unmanaged energy, rather than something qualitatively new and different.

“Security” is then the work of tactically managing this excess so that these energies don’t boil up and over into dangerous mass hackings. And I mean “dangerous” really honestly here. At a recent hearing before Congress, Bruce Scheier warned that DDoS attacks—which are, again, at root just a basic act of networked connectivity taken up to eleven—could feasibly target other networked infrastructures, like hospitals.6 Elevators. Ventilation systems. I dug up a report from last November from a town in Finland in which a DDoS attack turned off an IoT-automated heating system in the middle of winter.7 This shit’s real.

Our Networks Work By Leaking

So in this frame, I want to return to Wendy Chun’s arguments that I mentioned briefly at the top of this talk. In her recent work on networks and habituation, she argues that at the most fundamental level, our networks work by “leaking.” While we may think that our wireless network cards are just identifying available local networks, for instance, they are in fact constantly scanning, writing, and deleting all packets in range. What she calls “promiscuity,” and what I’ve called “sociability,” is central, not peripheral, to how our devices work with each other. In getting entangled with our fleshy lives and imbricated in our human sociality, the Internet of Things begins to make legible how we are also communicating by leaking. This is of course the central idea behind tracked advertising, such as the famous incident a few years back when Target could accurately predict whether or not a woman would become pregnant through her online purchasing habits.

It’s all too easy to lay the blame at end-user’s feet here, for “consenting” to such tracking, or for not taking their passwords seriously. Indeed, such a framing emerged at that same congressional hearing I mentioned earlier, in which Kevin Fu, a professor of computer science at the University of Michigan, argued for a “significant change in cyber hygiene,” without which IoT cannot be considered secure.8 He was arguing for governmental oversight of critical Internet infrastructures, which is certainly practical, but I note that the turn towards “hygiene” situates the human being as a kind of final weak link in a chain of security.

Doing so makes sense in the short term, but misconstrues, I think, what we’re framing as insecure. It’s not the human that’s insecure, but rather, as I’ve tried to argue, vectored sociable energies that can emerge from human and object alike. Without such a framing, we can’t begin to understand or embrace situations in which “openness” or “vulnerability” can be anything other than dangerous. The challenge I take up is to understand sociability and vulnerability in IoT as terrain open for the formation of solidarities, rather than an ever-interior turn towards the “local” as the single body or home.

Towards a Politics of Vulnerability

I would reconfigure the Internet of Things as an Assemblage of Sociable Energies (it’s not as catchy, I know), one in which we are mutually interdependent with objects that indeed can make our lives more interesting, joyous, practical or impractical. In such a frame, security, framed as the useful managing of tactical vulnerability rather than the delimitation of energetic possibility, must arise from both human and nonhuman agents. If our devices operate through insecurity, then they must be open to vectors through which attacks can occur. As I’ve argued, that Mirai targets insecure usernames and passwords reveals the human agent itself as a part of the security apparatus. Insecurity then moves both ways, as devices leave humans open to attack while humans leave devices open to attack. I think the chill in that sentence emerges more from our prevailing cultures of securitization, which outwardly demonize the sociable even as they demand it for operation. Of course, control can’t help but enter the frame: if we had platform cooperatives rather than centralized megacorps, this would probably be a very different talk.

But for now, we are caught between the rock and hard place of sociability and securitization. I’m not going to stick the dialectical landing here, but in such moments I want to turn back to Donna Haraway’s relentlessly call for a material and political embrace of our “joint kinship” with technology, our partiality and hybridity, our mutual introjection and prosthesis. Our devices operate by leaking and so do we: not only tracing out smells, secretions, rhythms, habits, and movements, but also by recognizing and responding to the traces of others. In this Assemblage of Sociable Energies, the human is a useful but not a special category; and “security” is the practice of kinship rather than isolation. This is an optimistic image, I know. It has no immediate answers for malicious actors, although I think that we have much to learn from those activists, including those in the prison abolition movement, who offer models for community policing and care. But I hope it begins to map territory for imagining a more capacious “we,” along lines of technology and humanity alike.

Krebs, Brian. “DDoS on Dyn Impacts Twitter, Spotify, Reddit.” Krebs on Security, 21 Oct. 2016, archive.is/nO8MY. Accessed 8 Dec. 2016. ↩︎

I adopt this “sociability” framing from Mittew, Teodor. “Do Objects Dream of an Internet of Things?” The Fibreculture Journal, no. 23, pp. 3–26, twentythree.fibreculturejournal.org/fcj-168-do-objects-dream-of-an-internet-of-things/. Accessed 8 Dec. 2016. ↩︎

Chun, Wendy Hui Kyong. Updating to Remain the Same: Habitual New Media. MIT P, 2016, pp. 52. ↩︎

Hui, Yuk. On the Existence of Digital Objects. U of Minnesota P, 2016, pp. 26. ↩︎

Kraus, Kari. “The Care of Enchanted Things.” Forthcoming in Debates in the Digital Humanities 2017, U of Minnesota P, 2017. ↩︎

Orcutt, Mike. “Security Experts Warn Congress That the Internet of Things Could Kill People.” MIT Technology Review, 5 Dec. 2016, www.technologyreview.com/s/603015/security-experts-warn-congress-that-the-internet-of-things-could-kill-people/. Accessed 8 Dec. 2016. ↩︎

Janita, “DDoS Attack Halts Heating in Finland amidst Winter.” Metropolitan.fi, 7 Nov. 2016, metropolitan.fi/entry/ddos-attack-halts-heating-in-finland-amidst-winter. Accessed 8 Dec. 2016. ↩︎

Orcutt. ↩︎